Abstract

This article examines the theological and logical tensions in Matthew Verschuur’s defense of the Pure Cambridge Edition (PCE) against my recent critique. It explores three interrelated issues: Providence, Special Revelation, and Verbal Equivalence. Verschuur claims the PCE is the providentially perfected form of the King James Bible, denying reliance on special revelation and asserting historical and textual analysis as his basis. However, this appeal to Providence raises an epistemic challenge: identifying a specific edition as divinely intended without explicit Scriptural warrant functions similarly to extra-biblical revelation. The article also contrasts my principle of verbal equivalence—where substantive doctrinal meaning suffices despite orthographic variation—with Verschuur’s insistence on exactness for the PCE. Ironically, Verschuur’s own framework requires verbal equivalence for earlier editions and translations to maintain their status as Scripture, creating internal tension. Ultimately, the debate centers on whether doctrinal certainty demands absolute precision or whether substantive fidelity is sufficient, and whether appeals to Providence can avoid collapsing into claims of special revelation.

[Sources: Verschuur, “Bryan Ross’ Attempted Fire Storm,” Dec. 6, 2025; Ross, “Inconsistent Logic & The PCE Position,” Dec. 2, 2025]

Introduction

The recent exchange between Matthew Verschuur (Bible Protector) and me (Grace Life Bible Church) sharpens long-standing questions in King James Bible advocacy: How does God guide the preservation of Scripture? What counts as the Word of God when editions differ? And is verbal equivalence sufficient, or must we have verbatim identicality down to letters and punctuation?

This article explores the nature of both of our claims and the underlying logic of this discussion.

What Verschuur Means by Providence

In his reply, Verschuur says the journey from the 1611 KJB through editorial refinements (e.g., Blayney 1769) to the PCE was guided by divine Providence—God steering ordinary historical processes (printers, editors, typographical standardization) toward an earthly form that is “exact to the letter.” He explicitly denies that he relied on private, mystical experiences or “Pentecostal” revelation to identify the PCE; instead, he claims a “believing textual analytical method” that discerns God’s providential hand in the printed history.

Providence, for Verschuur, is not new information from God; it is God’s orchestration of history that can be recognized through faithful analysis. The culmination of that providential trajectory, in his view, is the PCE as the resolved, letter-perfect standard.

What Counts as Special Revelation?

By contrast, special revelation refers to direct, supernatural disclosure: inspiration of Scripture, prophetic visions, and audible divine speech. I maintain that Verschuur relies on private interpretation (related to his Pentecostalism and Historicism). In contrast, Verschuur firmly denies receiving any new revelation about the PCE and insists his case is historical, textual, and providential.

Key distinction in theory:

- Providence = God guiding ordinary events; discerned by observation and argument.

- Special revelation = God directly telling you something new beyond ordinary means.

The Epistemic Tension: Does Providence Function Like Special Revelation?

Here lies the pressure point in the debate. Scripture does not specify which printed edition of the KJB is perfect. Yet Verschuur claims certainty that the PCE uniquely provides exact doctrinal nuance (every jot, tittle, letter, and punctuation mark). If that certainty cannot be derived from Scripture alone, and if it is not based on new revelation, it must arise from interpreting historical signs as indicators of God’s will.

I argue that this produces a functional equivalence to special revelation: the conclusion that the PCE is the perfect earthly standard is extra-biblical and asserted as divinely intended. Verschuur answers that it is simply a reading of Providence—not revelation—but the logical burden remains: a specific, divinely preferred edition is being identified outside explicit Scriptural warrant.

Even if we accept Verschuur’s denial of special revelation, his appeal to Providence blurs into revelatory territory insofar as it claims divine certainty regarding a particular edition that Scripture itself does not name.

Verbal Equivalence vs. Exactness

One of my cornerstone principles is verbal equivalence (See pages 5-10 of The Myth of Verbatim Identicality): the idea that variations in spelling, capitalization, punctuation, or minor wording across KJB editions do not corrupt the doctrinal content; the substantive meaning remains intact. I reject verbatim identicality as an unrealistic preservation model and argue that all editions of the KJB preserve substantive doctrine content even with minor orthographic differences.

Verschuur rejects verbal equivalence for the present, insisting on exactness: doctrinal nuance hangs on letters and punctuation (he cites Gal. 3:16 as a letter-sensitive doctrinal example). He contends the PCE alone achieves “exact sense” across the entire Bible and that differences in orthography (e.g., alway vs. always) affect meaning.

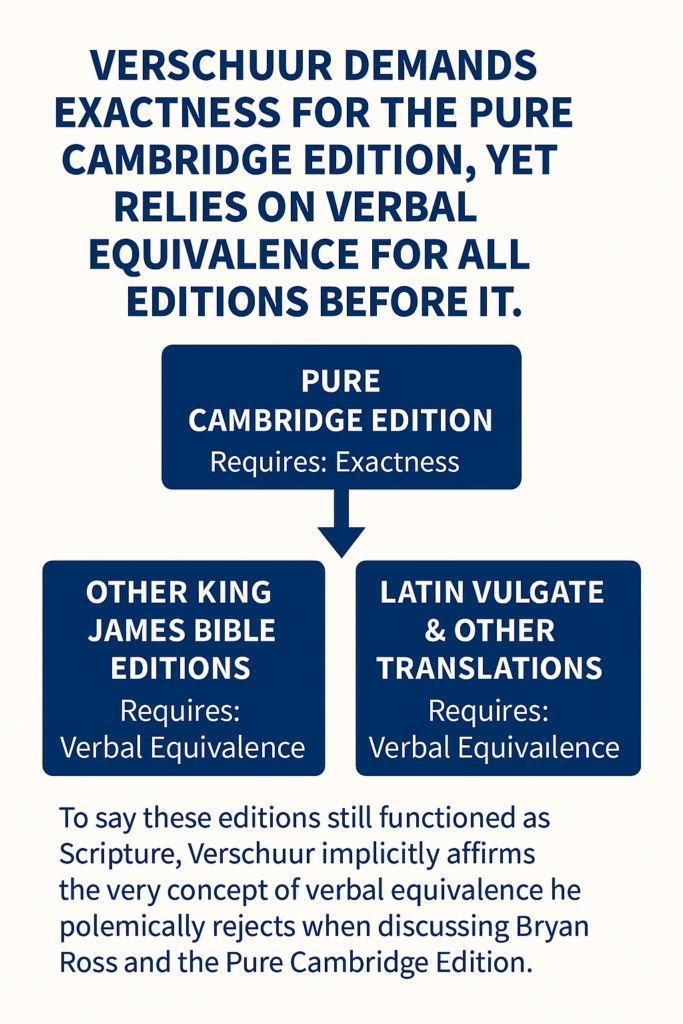

The Hidden Irony: Verbal Equivalence Before the PCE

Despite rejecting verbal equivalence, Verschuur maintains that pre‑PCE editions of the KJB (and even the Vulgate) still were the word of God to those who used them—he locates this in his seven levels framework, where Level 3 (“Scripture on Earth”) recognizes “substantive” faithfulness even when exactness is lacking, while Level 7 (the PCE) provides full, letter‑perfect exactness.

To affirm earlier KJB editions and pre‑KJB translations as still Scripture, Verschuur must allow that they conveyed the substance of God’s Word without full exactness, which is, in practice, verbal equivalence. Thus, his position demands verbal equivalence for pre‑PCE history, while he denies it for the present, producing an internal tension.

Functional Exclusivity and the “Seven Levels”

Verschuur’s seven levels attempt to reconcile the tension by distinguishing degrees of purity:

- Mind of God

- Perfect Form in Heaven

- Scripture on Earth (substantively faithful copies)

- Textual Purity (Received Text)

- Translation Purity (KJB best translation)

- Edition Purity (editing progress)

- Resolved Exact Form (PCE)

*Verschuur’s enumeration and biblical citations: Ps 40:7; Ps 119:89; Dan 10:21; Heb 8:5; 9:19, 23*

This framework lets him say non‑PCE editions are the Word of God “substantively” (Level 3), while only the PCE provides exhaustive exactness (Level 7). It is high time for Brother Verschuur to admit that the premises (doctrine depends on exact letters; only PCE is exact) logically exclude other editions from being “pure and perfect,” yielding functional exclusivity despite Verschuur’s verbal denial.

Where the Debate Lands

- On Providence: Verschuur’s use of Providence aims to avoid claims of new revelation. Yet, because Scripture doesn’t explicitly demarcate an edition, asserting the PCE as God’s intended exact standard creates an epistemic burden that resembles extra‑biblical divine direction.

- On Special Revelation: Verschuur denies it; meanwhile, his certainty about the PCE behaves like it.

- On Verbal Equivalence: I embrace it; Verschuur rejects it now, but his own logic requires it historically to keep non‑PCE editions within the umbrella of “Scripture.”

Therefore, my critique stands: either exactness is essential for the Word of God (which would exclude non‑PCE editions), or substantive meaning suffices (which affirms verbal equivalence). Verschuur attempts to hold both by stratifying “levels,” but the functional outcome still privileges the PCE as the only fully adequate edition, thereby undercutting his non‑exclusive rhetoric.

Conclusion

Matthew Verschuur’s defense of the PCE ultimately collapses under the weight of its own premises. He insists that doctrinal precision depends on absolute exactness—every letter, punctuation mark, and orthographic detail—yet simultaneously affirms that earlier editions and even the Latin Vulgate were the word of God. This creates an irreconcilable tension: if exactness is essential for Scripture to function fully, then non-PCE editions fail that test; if substantive fidelity suffices, then his rejection of verbal equivalence is incoherent.

His appeal to Providence compounds the problem. By claiming that God guided history to produce the PCE as the perfected standard, Verschuur asserts a specific divine intention not revealed in Scripture. While he denies special revelation, his certainty about the PCE’s unique status functions like extra-biblical revelation in practice. The seven-level framework, intended to reconcile these contradictions, only stratifies the inconsistency: it tacitly relies on verbal equivalence for pre-PCE editions while polemically rejecting it for the present.

In short, Verschuur’s argumentation is internally inconsistent. It demands exactness yet tolerates approximation, denies verbal equivalence yet depends on it historically, and appeals to Providence in a way that blurs into revelatory certainty. Therefore, my critique stands: either exactness is the standard—excluding all but the PCE—or substantive meaning suffices, affirming the very principle Verschuur rejects. His attempt to hold both positions is not a nuanced synthesis but a logical contradiction.

Pastor Bryan Ross

Grace Life Bible Church

Grand Rapids, MI

Wednesday, December 10, 2025

Resources For Further Study

Lesson 47 The Method of Preservation Providential or Miraculous